merge vs. rebase: choosing the right tool

I've seen a few protips here claiming that git pull is evil or dead or something. It's a little more complicated than that. I'm going to try and explain what's what and why and what it means for you.

First off: git pull is not dead – even if you don't generally like merge commits. By default, git pull merges your commits, but it can be configured to rebase instead (config settings branch.autosetuprebase and branch.yourbranch.rebase</code>). Even then, there are good reasons to use or not use either of the two.

We're going to need these terms:

- Local branch: a branch you're working in.

- Upstream branch: a branch that your local branch is based on and that you'd like to get updates from.

Rebasing

The good: in short, rebase takes your commits and puts them "on top of" upstream history, i.e. it pretends you made your commits after all the new ones. This tends to look nice, and it can make it easier for the maintainer of a fork/upstream repository to integrate your changes. Both of these are good things, of course.

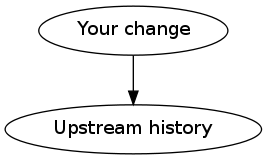

The bad: if you rebase commits that you've already shared with others (e.g. by rebasing stuff you already pushed earlier and then using git push -f), things go sour fast. Here's your history prior to rebasing:

[1]

[1]

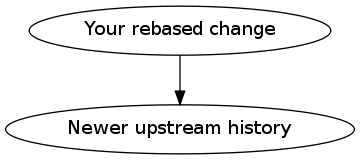

And here's your history after rebasing:

[2]

[2]

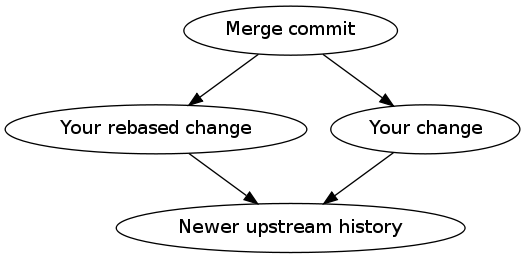

Suppose someone else has a copy of the history in [1] and uses git pull (yes, people still do that)... then they get this:

[3]

[3]

Ouch!

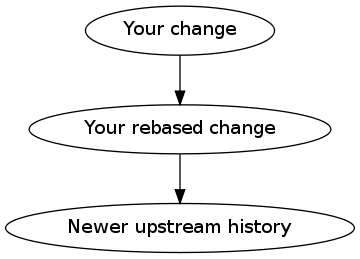

But okay, maybe rebase will be more awesome. And, indeed, in some simple cases, it will magically do the right thing... but if the new upstream changes are closely related to your own changes, someone might get this after a git pull --rebase:

[4]

[4]

Woah, what happened there? git rebase could no longer detect that the two commits (rebased and not) are equivalent, so it put the non-rebased one (that only exists locally for this user now, because you rebased it away in the upstream repository) on top of the rebased one (which it considers upstream because the upstream branch has it and the user's local branch doesn't). Ouch again!

Finally, rebase linearizes merge commit by default. This means that if one of your local commits is a merge commit, it won't be after rebase is done – it will turn into a strangely ordered series of all the commits introduced by the original merge. Rebase does have a mode to preserve merges, but you have to remember to use it. So, rebase and merge are a bit like oil and water – they don't mix without an emulsifier (the extra flag).

Merging

The good: merges work spectacularly well for even the wildest distributed collaboration scenarios. You can merge back and forth to your heart's content and Git will almost always figure it out.

In addition, it's worth pointing out that merge commits can serve as a valuable record of the fact that a specific person integrated a specific set of changes into a branch. If you want to be able to trace back what integration work happened and when, rebase will actually make your life more difficult.

The bad: as others have pointed out, excessive merging makes your history very complicated. Git's history viewing tools can be told to simplify history (e.g. git log --first-parent – works particularly well if you write good commit messages for your merge commits), but often enough a straightforward series of commits simply works best.

Another big problem with merges is that it's not possible to undo them once you've published them – much like it's a bad idea to rebase published commits. You might be tempted to think that git revert with the -m option will undo merges, but it doesn't: it only undoes the changes. If you do a subsequent merge of the same branches, git won't notice that the old merge commit was reverted (because a revert is technically a completely independent commit), so it will never merge the previously merged commits again. Instead, it will merge only the newer commits on the upstream branch. I can't really think of a scenario in which this is sane.

Fast-forwards

There's a class of changes in which merge and rebase do exactly the same thing (by default): when you have no local changes at all, both merge and rebase will simply bring you up to date by "fast-forwarding" your local branch to the same state as the upstream branch. You can force git merge to create a merge commit, though, with the option --no-ff – this way you'll still get an explicit record of the merge.

Squashing

You can use git merge --squash to create a "big commit of everything" instead of a merge commit. It'll roll all of the upstream changes into a single big commit. This is usually not useful because if the commits were well-crafted, you now have less information and structure in your history than you did before. It can be convenient if you want to integrate the final version of a fairly small change, though.

What to choose

- If you're a contributor, use rebase whenever you can get away with it. Try to avoid contributing something in which you've made merge commits – it'll make things harder for the maintainer/integrator.

- If you're a maintainer, it really depends on the scope of the set of commits you're integrating, and on personal taste. I like to rebase or cherry-pick small changes but merge interdependent series of commits, especially if they were developed largely independently from the "official" development work on the project.

What to avoid

- Avoid "experimental" merges. If you push/publish a merge, you'd better be very sure that the merge is good.

- Don't use both merge and rebase on the same bit of history (i.e. local-only commits).

- Don't use squash merges if you want to merge/rebase the same branches again later on.

- Don't alter your history once it's published. Both merge and rebase will screw things up. Anyone who tries to combine both the old and the new history will have to do extra manual work.

- If you do accidentally combine two versions of history, for the love of everything, don't inflict the resulting abomination on anyone else. Just start over.

Related protips:

Written by Jan Krüger

Related protips

2 Responses

"Don't alter your history once it's published."

I think you're alright to do this if you're working in your own feature branch and are, say, tidying up a pull request you've been working on after making further changes.

@leemachin yeah, but whenever your feature branch can be seen by others, it must be clear to them that they should expect the branch to be rewritten at any time. This should be the case if the branch name suggests shortlivedness and volatility.