The Best Drinking Temperature for Coffee: Precision, Perception, and the Pursuit of Flavor

Coffee professionals often devote enormous attention to origin, processing method, roast profile, grind size, and extraction yield. Yet one of the most immediate and decisive variables in the sensory experience of coffee is frequently overlooked: drinking temperature. The temperature at which coffee is consumed directly influences aroma volatility, sweetness perception, acidity clarity, bitterness intensity, mouthfeel, and even aftertaste persistence. It shapes not only how we taste coffee, but whether we enjoy it at all.

In this comprehensive guide, I will examine the best drinking temperature for coffee from a professional standpoint—drawing on sensory science, thermodynamics, extraction theory, and service standards. We will explore how temperature affects flavor perception, how it interacts with roast level and brew method, and how to manage temperature in both café and home environments. By the end, you will understand why temperature is not simply a matter of preference, but a critical control point in delivering an exceptional cup.

The relationship between coffee temperature and caffeine content is often misunderstood. Temperature primarily influences extraction rate, not the inherent caffeine content of the coffee beans. Caffeine is highly water-soluble and extracts relatively early in the brewing process. When brewing with hot water—typically between 195–205°F (90–96°C)—caffeine dissolves quickly, often within the first minute of contact. Higher brewing temperatures accelerate extraction, but once caffeine is fully dissolved, increasing temperature further does not significantly increase total caffeine content.

In contrast, cold brew uses low temperatures and extended steep times (12–24 hours). Although the water is cold, the long contact time allows comparable or even higher total caffeine extraction, especially when concentrated brewing ratios are used. Therefore, final caffeine levels depend more on brew ratio, grind size, and contact time than on temperature alone.

Serving temperature also does not change caffeine content. Whether coffee is consumed hot or iced, the caffeine molecule remains chemically stable under normal beverage conditions. However, colder coffee may be consumed more quickly or in larger volumes, indirectly increasing intake.

To accurately estimate caffeine consumption across different brewing temperatures and styles, a caffeine calculator is useful. By inputting brew method, coffee dose, water volume, and serving size, a caffeine calculator provides a more precise estimate than relying on temperature assumptions alone.

1. Temperature and Sensory Science: Why Heat Changes Flavor

To understand the best drinking temperature, we must first understand how temperature influences sensory perception.

1.1 Aroma Volatility

These compounds evaporate more readily at higher temperatures. When coffee is very hot (above approximately 70°C / 158°F), volatile compounds rapidly vaporize, creating a strong aromatic burst. However, excessive heat can overwhelm the olfactory system, masking nuance and complexity.

As coffee cools to a moderate range (roughly 55–65°C / 131–149°F), aroma release becomes more balanced. At this point, individual notes—floral, fruity, nutty, caramelized—are more distinguishable.

Below 45°C (113°F), volatility decreases significantly. Aromas become muted, and the cup may feel flat or dull even if the chemical composition has not changed.

1.2 Taste Perception

Temperature alters how we perceive sweetness, acidity, and bitterness:

- Sweetness is more pronounced at moderate temperatures.

- Acidity becomes clearer as coffee cools.

- Bitterness can feel more aggressive at higher temperatures, but paradoxically more persistent at lower temperatures.

At extremely high temperatures, pain receptors in the mouth may be activated. When this occurs, nuanced flavor perception is suppressed. The sensory system shifts from analysis to protection.

1.3 Texture and Body

Heat influences viscosity perception. Warmer liquids feel thinner; cooler liquids feel denser. This is partly psychological and partly physiological. Thus, a full-bodied coffee may feel lighter when served too hot, while a medium-bodied coffee can feel heavier as it cools.

2. Brewing Temperature vs. Drinking Temperature

It is essential to distinguish between brewing temperature and drinking temperature.

- Brewing temperature typically ranges from 90–96°C (194–205°F) for most methods.

- Drinking temperature is considerably lower.

Water must be hot to extract soluble compounds effectively. However, once extraction is complete, the beverage must cool to a range that supports sensory clarity.

Confusion between these two temperatures often leads consumers to believe coffee should be consumed extremely hot. In professional service, that assumption is inaccurate.

The relationship between coffee temperature and coffee grind size is fundamentally tied to extraction kinetics. Temperature affects how quickly soluble compounds dissolve, while grind size controls the surface area available for extraction. Together, they determine balance, strength, and flavor clarity in the cup.

At higher brewing temperatures—typically 195–205°F (90–96°C)—water has greater kinetic energy, increasing extraction speed. Because extraction occurs more rapidly, a slightly coarser grind may be appropriate to prevent over-extraction, particularly for immersion methods. If the grind is too fine at high temperatures, bitter compounds and excessive solids can be extracted, leading to harsh flavors.

At lower temperatures, such as in cold brew, extraction occurs much more slowly. To compensate, brewers may adjust grind size depending on steep time. Although cold brew usually uses a coarse grind, reducing temperature sometimes requires a modestly finer grind if steep times are shortened. The key is balancing temperature and surface area so extraction remains controlled.

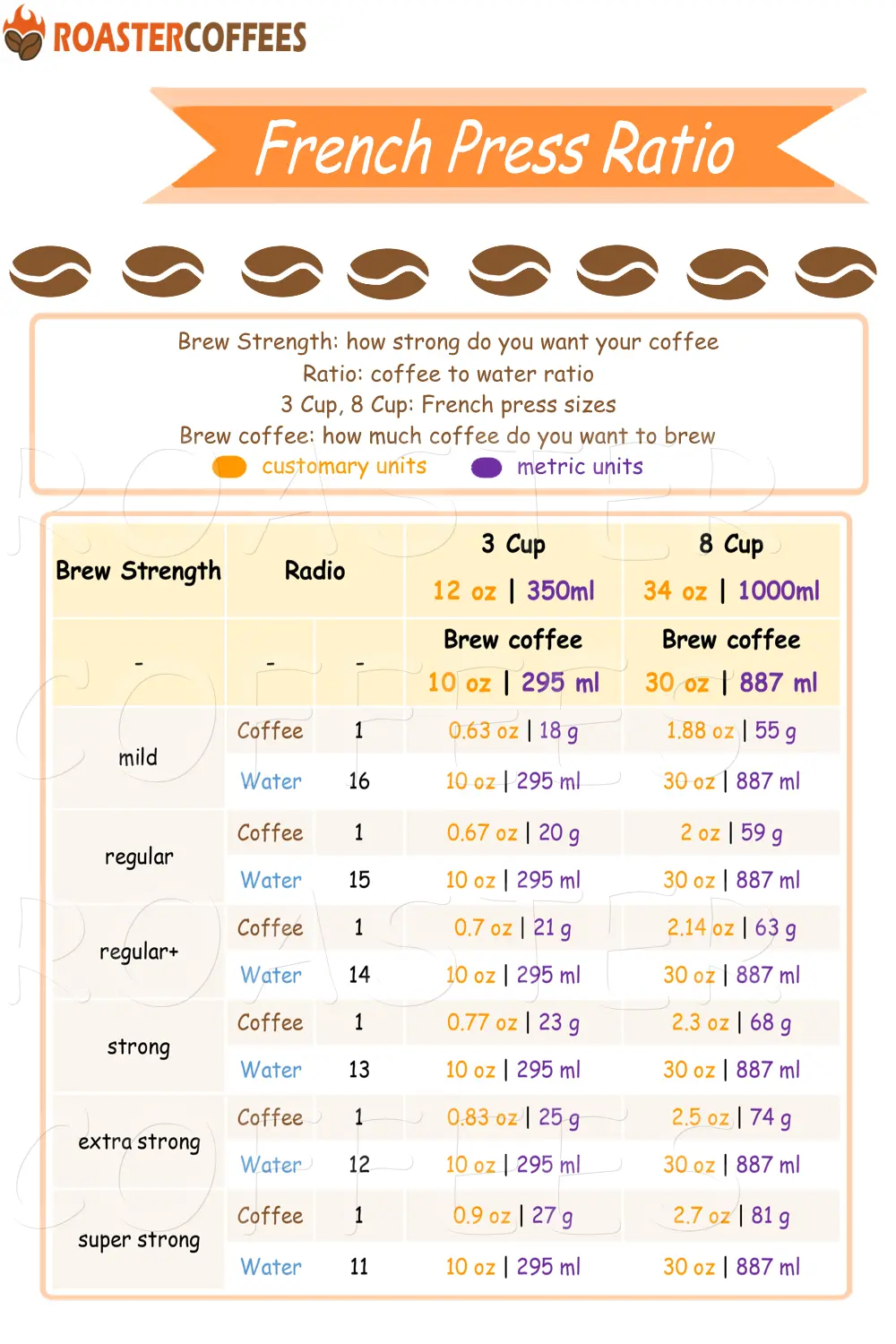

A coffee grind size chart is a practical reference for aligning grind settings with brewing temperatures and methods. It visually correlates grind categories—extra fine to coarse—with techniques like espresso, pour-over, French press, and cold brew. By consulting a coffee grind size chart and adjusting for temperature, brewers can fine-tune extraction efficiency and maintain consistency across different brewing conditions.

3. The Ideal Drinking Temperature Range

Based on sensory research, industry standards, and practical experience, the optimal drinking temperature for black coffee generally falls between:

55–65°C (131–149°F)

This range provides a balance between aromatic release, sweetness perception, acidity clarity, and overall drinkability.

Let us break it down further:

| Temperature Range | Sensory Characteristics |

|-------------------|------------------------|

| Above 70°C (158°F) | Aroma is intense but indistinct; sweetness is suppressed; acidity is muted; risk of oral discomfort increases |

| 60–65°C (140–149°F) | Aromas are expressive yet defined; sweetness becomes noticeable; acidity gains clarity; body perception is balanced |

| 50–55°C (122–131°F) | Complexity peaks for many specialty coffees; fruit notes and floral tones shine; bitterness becomes more apparent if present |

| Below 45°C (113°F) | Aromas diminish; acidity may feel sharp; bitterness lingers; overall liveliness decreases |

For most specialty-grade coffees, the most expressive window lies between 55°C and 60°C (131–140°F) .

4. Roast Level and Temperature Interaction

Different roast levels respond differently to temperature shifts.

4.1 Light Roasts

Light-roasted coffees are structurally dense and retain higher acidity and complex aromatics. When consumed too hot, their acidity may feel sharp and unbalanced. As they cool into the 55–60°C range, sweetness emerges, and acidity becomes structured rather than aggressive.

Light roasts benefit significantly from allowing a brief cooling period before evaluation.

4.2 Medium Roasts

Medium roasts often demonstrate balanced caramelization and moderate acidity. They are relatively forgiving across temperature ranges but perform best between 58–63°C (136–145°F) , where sweetness and body are harmonized.

4.3 Dark Roasts

Dark roasts emphasize roast-derived bitterness and carbonization compounds. When consumed very hot, bitterness may be masked by temperature. As they cool, bitterness becomes more pronounced. For dark roasts, slightly warmer consumption (around 60–65°C ) often yields a more balanced experience.

5. Brew Method and Temperature Behavior

Each brew method influences how coffee cools and how temperature affects perception.

5.1 Pour-Over

Pour-over coffee typically has clarity and pronounced acidity. It cools relatively quickly due to thin ceramic vessels and lower beverage mass. Its optimal tasting window often appears around 55–60°C .

5.2 French Press

French press coffee retains oils and fine particles, increasing body and heat retention. The heavier texture may feel more pleasant slightly warmer, around 58–63°C .

5.3 Espresso

Espresso is served in small volumes (25–40 ml). It cools rapidly. Extraction temperature is high, but drinking temperature should ideally fall below 65°C. Many professionals find espresso most expressive between 50–55°C .

5.4 Milk-Based Drinks

Milk changes the equation significantly. Steamed milk is commonly heated to 55–65°C for service. Above 70°C, milk proteins denature excessively, sweetness diminishes, and texture deteriorates.

For beverages such as cappuccino or latte, 55–60°C provides optimal sweetness and mouthfeel.

6. Heat Retention: Cup Material and Environment

Temperature management extends beyond brewing.

6.1 Cup Material

- Thin porcelain: Rapid heat loss, enhanced aroma concentration

- Thick ceramic: Better heat retention, slower cooling curve

- Double-walled glass: Insulation without external heat

- Paper cups: Fast cooling, variable insulation

- Preheated cups: Essential for maintaining initial serving temperature

Professional service requires preheating cups to prevent rapid thermal drop.

6.2 Ambient Conditions

Room temperature, airflow, and humidity influence cooling rates. In colder environments, beverages lose heat quickly, shifting the sensory window earlier than expected.

7. Safety Considerations

Extremely hot beverages can cause burns. Regulatory bodies in various countries have examined safe service temperatures, particularly after well-known litigation cases involving excessively hot coffee.

From a professional standpoint, serving coffee above 70°C is unnecessary for flavor and increases risk. The goal is not maximum heat but maximum expression.

8. Cold Brew and Iced Coffee: A Temperature Contrast

Cold brew coffee is extracted at low temperatures and served chilled. Its sweetness and low perceived acidity are partly due to extraction chemistry and partly due to temperature.

At lower temperatures:

- Acidity perception decreases

- Bitterness softens

- Body feels fuller

This demonstrates how profoundly temperature shapes flavor interpretation.

9. Sensory Evaluation Across Cooling Stages

Professional cupping protocols intentionally evaluate coffee as it cools. This is not incidental—it is essential.

As coffee cools:

- Aromatic intensity decreases

- Sweetness increases

- Acidity sharpens and clarifies

- Defects become more detectable

A high-quality coffee remains pleasant across a wide temperature range. Inferior coffees often collapse as they cool.

10. Practical Recommendations for Home Brewers

To optimize drinking temperature:

- Preheat cups with hot water

- Allow brewed coffee to rest 2–4 minutes before drinking

- Taste in stages rather than immediately

- Use an instant-read thermometer if precision is desired

- Avoid microwaving brewed coffee, as reheating alters flavor balance

Patience is a tool of professionalism.

11. Café Service Standards

For cafés aiming at quality:

- Serve black coffee at approximately 60–65°C

- Steam milk to 55–60°C for optimal sweetness

- Educate customers about flavor evolution as coffee cools

- Avoid defaulting to excessive heat to prolong perceived warmth

Temperature should be deliberate, not accidental.

12. Psychological Expectations and Cultural Norms

Cultural habits influence temperature expectations. In some regions, extremely hot coffee is associated with freshness. In specialty coffee culture, moderate temperatures are associated with quality.

Consumer education bridges this gap. When customers understand that cooler coffee reveals more flavor, acceptance increases.

13. Conclusion: Temperature as a Final Extraction Variable

The best drinking temperature for coffee is not arbitrary. It represents the final stage of extraction—not chemical extraction, but sensory extraction.

While brewing extracts compounds from ground coffee, drinking temperature extracts meaning from those compounds. Too hot, and complexity is suppressed. Too cold, and vibrancy fades.

For most black coffees, the optimal window lies between 55°C and 65°C , with peak expression often around 58–60°C . Milk-based beverages perform best slightly lower, typically 55–60°C .

Ultimately, temperature management is an act of respect—for the farmer who cultivated the cherries, the roaster who developed the profile, the barista who executed the extraction, and the drinker seeking pleasure in the cup.

Precision in coffee does not end at brewing. It continues until the final sip.

References: